Scrums and mauls are the two great dominance contests within the game of rugby. Marked superiority in either of these forms of engagement can affect the morale of both teams in a way that a corresponding supremacy at say the lineout does not.

Forward packs spend countless hours developing scrum technique but very much less attention is given to the maul, particularly in a defensive situation. Scrums are also elaborately structured whereas mauls tend to be chaotic. To a large extent this is due to the relative extent to which the two are regulated by the Laws of Rugby. Law 20, relating to the scrum, comprises three times as many pages as Law 17 pertaining to the maul.

Unlike the scrum, the Laws are largely silent on what players can do in the maul. Within the maul itself the most relevant clauses are that "Players joining a maul must have their heads and shoulders no lower than their hips" (17.2 (a)); they "must endeavour to stay on their feet" (17.2 (d)); and "A player must not intentionally collapse a maul" (17.2 (e)). Thus there remains considerable latitude for creativity.

One very marked difference between the two contests is that in the scrum either pack, whether having the feed or not, has the opportunity to establish dominance and drive the other pack back. By contrast it is very rare in the maul for the side not in possession to gain significant ground. This is largely due to the fact that the team with the ball is able to surreptitiously transfer the ball laterally from hand to hand so that the push from their opponents bypasses the ball-carrier, allowing him to be driven forward more or less unimpeded.

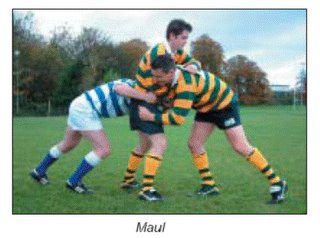

I believe that players can be trained to maul much more effectively and the secret is body height. Note the photo reproduced from the International Rugby Board's online version of the Laws of Rugby. It is intended to show the player involvements necessary for a maul to be formed. But it is also very instructive in illustrating body heights typically adopted in the maul. The ball carrier is standing upright, making no attempt to crouch. His team mate in attempting to seal off the ball has his shoulder at chest height of the ball-carrier. Their opponent has bound on the ball-carrier at waist height. None of these players have their legs positioned to exert an effective forward shove.

The body height adopted by the first players engaging from each team usually defines the height of their side of the ensuing maul. Subsequent players typically bind against the buttocks of the players in front of them. Players arriving at a maul tend to simply bend at the waist when joining the contest.

Compare the likely height of this maul with the body height of the same players in a scrum situation. It can be confidently anticipated that body heights would be at least 300mm lower in a scrum than in a maul.

If the defending player in the photo were to bind around the thighs of his opponent rather than the waist, he would create a platform for his team mates to bind at something close to scrummaging height. Each of the players is then likely to have optimal hip and knee joint angles for generating forward momentum. It might even be advantageous for players to adopt the second-rower's technique of binding between the thighs of the player in front, whether team mate or foe. The one essential requirement is that players packing low secure a very firm grip to avoid being penalised for going to ground.

While front row players in the scrum are prohibited from "lifting or forcing an opponent up" (20.8 (i)), there is no corresponding restriction in relation to mauls. Although lifting is treated as "dangerous play" in the scrum, it does not have the same connotation in the maul where players are bound in an unstructured way and not confined or compressed as in the scrum. With his shoulder under his opponent's buttocks a player is ideally placed to drive up, forcing the opponent to give ground.

While mauls are often formed in an unstructured way, many of them emerge from static engagements such as the lineout or where the ball is being contested after a tackle. In such a situation a well-drilled team would have the opportunity to rapidly adopt a pseudo-scrum formation and drive forward. Not only are they likely to gain advantage in that particular maul, but the practice of adopting biomechanically superior body positions will undoubtedly be energy-conserving over the course of a game.

rugby

rugby scrum

rugby maul

bodyheight

Laws of Rugby