Introduction

Despite the undoubted importance of efficient force delivery in the scrum, there is very limited published material addressing the actual dynamics of force delivery.

Powerful scrummaging is dependent on appropriate body position and limb alignment, not just in the relatively static situation immediately after engagement but throughout the entire contest of the scrum. Much of what passes for best practice in scrum formation reflects a failure to critically examine the actual geometry and mechanics of body position and how these change during the scrum contest.

I believe that an optimal configuration of body position and limb alignment on engagement involves hip and knee angles each set at 90° with both trunk and shank being parallel to the ground. During the scrum, hip and knee joints should move synchronously so that their angles remain equal. The hips may sink slightly relative to the shoulders but trunk and shank should remain parallel.

Body height and joint angles – what the experts advocateModern thinking on scrummaging usually advocates consistency of body shape for all participants regardless of position, with the feet approximately shoulder width apart and toes level. There also seems to be general agreement on the need for the trunk to be horizontal or for the shoulders to be slightly higher than the hips. (Greenwood, 1978;

Smith, 2000;

NSWRU, 2004;

Vickery;

O'Shea, 2004:

Argentinian Bajada method)

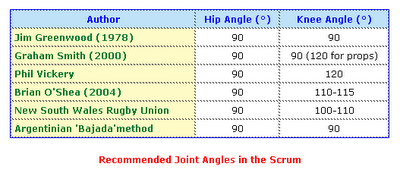

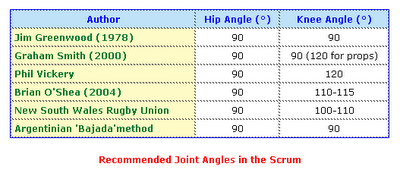

However, when joint angles are discussed there is substantial divergence of opinion on the appropriate angle at the knee joint:

Jim Greenwood, Total Rugby, 1978More than three decades on Greenwood's book, though overtaken by a succession of Law changes, remains a rugby classic. Its underlying logic is compelling. The figure below summarises his views on body position:

Greenwood argued that the optimal pushing position required hips below shoulders, 90° joint angles at hip and knee, and "knees near the deck." It can be seen from his drawing 1c above that the trunk and shank are parallel.

The figure also considers the effect of different joint angles on force delivery, and this is further discussed elsewhere in the book:

"Thighs approximately vertical. It's obvious that the more acute the angle of the knee the greater the potential range of the drive, but the more strength is required to initiate it. … [Y]ou only have to go into the full-flexed position to realise that a drive from that position is very much slower and more difficult than a drive from a half-squat. Players tend to assume the position in which they feel most capable of a snap drive. On the other hand, the smaller their degree of flexion the smaller the range of drive. For a six-foot player, a flexion of 90° at the knee produces a potential forward movement of about a foot, which allows for a snap drive, and the necessary continuation shove. That is more than enough for all practical purposes, and may well be seen as a maximum."

Greenwood also emphasises pack height:

"Shoulder height in the front row determines how low the pack can get. From every point of view, the lower the pack gets the better - provided the hooker is capable of striking. … Against the head, it's better to get even lower than usual. What this comes to is that the props get closer and closer to the basic driving position, with their feet further back and wider, their hips correspondingly lower, and their upper bodies close to horizontal. This has two advantages: it restricts the opposing hooker's strike, and may even prevent it, and it ensures a more powerful and effective drive. It's worth pointing out that most scrum-machines are set too high to allow effective low scrumming practice."

Smith emphasises body position. "Each player must take up a position by which the force generated by the large muscles of the lower body, the quadriceps and gluteals particularly, can be transmitted effectively and SAFELY through the spine, the shoulders and the neck."

"The power the legs can produce or resist is conditioned by the angle at the knee. With the thigh vertical, or near vertical, this angle should be maintained between 90° and 120°. The greater angle will be required by the props who need to be more upright in stance in order to provide a base on which, the locks can push. The other forwards can however, adjust their positions to achieve 90° at knee."

Smith examines the consequences of a prop being experienced enough and strong enough "to alter the height of the scrummage quite legally." and "produce a significant disruption of the opposition scrummage. A prop can thus legally force his opponent to scrummage lower, at a height he finds uncomfortable, and which is mechanically inefficient."

An opponent who is unequal to this pressure will normally react in one of two ways. Firstly, he can move his feet further and further back to relieve the discomfort, as in the figure below:

He may be forced to

"take his feet so far back that he goes to ground flat on his face … Even if he doesn't go to ground the position he is forced to adopt allows less and less of the power generated behind him to be transmitted though on to the opposition."

Alternatively, the prop that is being forced to scrummage too low may

"bend forward at the hip, his head gradually getting well below the line of the hip," as in the figure at right.

"Because of the pressure from behind by his own lock the prop can be put into a seriously uncomfortable position. He's caught in a vice, and his position becomes even more unpleasant should his superior opponent drive forward at him."

This document states that "almost 99% of all scrimmaging problems can be related directly to the body shape of the participant(s)." Amongst its prescriptions for "correct body shape" are:

"Knee bend (100 - 110° approx) directly beneath hips will assist in generating and transferring weight.

"High, steady hips will allow those players behind to apply force through a near vertical surface. The hips should NOT at anytime be higher than the shoulders."

Further on there is a series of images showing the sequence of scrum formation. The final image, reproduced at left shows the engagement. My rough scaling indicates that the loose head prop's hip and knee angles are around 90° and 120° respectively. However it appears that his shoulders are about 15°lower than his hips. This would not only be illegal but would place him and his fellow front rowers in an inherently unstable situation. He is not in a position either to support his own bodyweight or to generate a horizontal shove.

"The knee must be bent to generate the explosive power of the legs. If only slightly bent, there will only be a small, but quick, motion forwards. If a deep bend, the forward movement will be slow but be farther. Straight legs prohibit players going backwards but there is little forward momentum. The ideal is a vertical thigh with an angle of about 120 degrees between the thigh and the calf which should provide the required thrust."

In discussing body shape O'Shea specifies:

"A bend at the knees which provides an angle of approximately 110-115°, which permits power generation by the legs. This position is a 'trade-off' between the generation of dynamic power and the length of push that can be achieved. If the bend at the knees is not adequate the distance gained by the push is hardly worthwhile. If the bend at the knees is too great the loss of mechanical advantage makes it difficult to be dynamic."

He does not deal directly with the hip angle but calls for a "straight, flat back" and "high hips" that "should not be higher than the shoulders." Significantly, when illustrating individual common faults, he uses a diagram, reproduced above. where the player with correct technique appears to be in the 90-90 position.

Argentinian teams are renowned for the effectiveness of their scrummaging and the central importance of the scrum to their game. From an early age, Argentinian forwards are schooled in the 'Bajada' or 'Bajadita,' a radically different scrum method invented in the late 'Sixties by the legendary Francisco Ocampo.

A defining characteristic is the 'Empuje Coordinado' or 'Coordinated Push.'

"The scrumhalf gives a three part call after the "engage". On "pressure" all members of the pack tighten their binds and fill their lungs with air. On the call "one" everyone sinks; the legs at this point should be at 90 degrees. On "two" the pack comes straight forward while violently expelling the air from their lungs. A key note is that nobody moves their feet until forward momentum is established. If the first drive is insufficient the scrumhalf begins the call again and the opposing pack is usually caught off guard and pushed back." Rugby Union from the Virtual Library of Sport

Sergio Espector, a Level 3 Argentinian coach, recently summarised the main features of the Bajada. After the engagement he stipulates that "all eight players must flex their knees to 90 degrees ... [and] players must never move their feet off the ground until they overcome their opponents and have positive inertia."

The Bajada is recognised as an extremely effective and powerful form of scrummaging.

Summarising the views of these authors:

Analysing joint angles in the scrum

We can visualise the body in scrummaging mode as a system of skeletal levers articulated primarily at the hip and knee joints. The levers are activated by muscular contraction of the relevant extensor and flexor muscle groups. The task is to determine optimal ways to operate those levers to achieve the desired goal of delivering force in the horizontal plane, given that the primary objective of any pack is to effectively resist and, if possible, overcome the horizontal weight force generated from the opposing pack.

The figure above depicts the limb configurations of a player packed into a scrum with his hip and knee angles both at 90°. (For the sake of illustration I have assumed that the player is 1850mm tall with trunk, thigh and shank lengths of 650mm, 460mm and 480mm respectively.) In order to compare the 90-90 configuration with that advocated by some of the experts listed above, the figure below shows how the body position of the player would change if he retained the 90° hip angle but increased his knee angle to 110°.

As can be seen in the figure a knee angle of 110° requires the shank to slope upward 20° above the horizontal. This results in the height of the trunk above ground level rising by 160mm, a quite substantial difference when packs are preparing to engage.

A pack using the 90-110 configuration and therefore accustomed to training and playing with an obtuse knee angle will be disadvantaged if forced lower on engagement. The front row will have no choice but to reduce their knee angle if they are to avoid packing illegally, i.e., with hips above shoulders, and the rest of the pack will have to similarly adjust. Quite apart from the illegality, a failure to adjust the knee angle places the front row in an essentially unstable body position with the risk of the shoulders being driven even further below hip height.

As with the squat exercise, when players under severe load go into a deeper joint contraction than they are accustomed to, they have to operate in a 'zone of discomfort.' The cohesion of the pack is threatened; players may be forced to give ground and at the very least are not in a position to generate a powerful forward shove.

By contrast, a pack accustomed to function with a 90° knee angle can quite comfortably cope if the engagement takes them higher than they would prefer, as they are still operating in the range of joint angles they are familiar with.

Effective scrummaging requires coordinated and synchronised activity by all eight members of a pack. It is also essential that throughout the whole scrum engagement the pack remains in a position to initiate or effectively repel considerable force. Adoption of a 90-90 joint configuration facilitates both objectives.

Coordinated action can be readily achieved if players are trained to start from a common orientation of the joints whatever their playing position, and then to keep their shanks and trunk parallel at all times. This means that the joint angles at hip and knee remain equal as the pack drives forward. Each player is effectively contributing to the collective transmission of force along the line of their backs.

Muscles generate most force in the mid range between full extension and full flexion. From a starting point of 90-90 the leg extensors typically remain operating within that efficient range even when the pack achieves a significant shunt forward. Figure 8 illustrates how joint angles change following a push forward of 300mm. As Greenwood suggests, a "forward movement of about a foot ... may well be seen as a maximum" without repositioning of the feet. As can be seen both joint angles have extended to 138°, but this still leaves the players in a position to continue their forward momentum if necessary. Note that both the trunk and shanks have dropped 6° below the horizontal.

The 90-90 joint alignment provides the optimal platform for horizontal force delivery which can be sustained through a considerable range of movement forward, while simultaneously tending to force the opposing pack to function within a 'zone of discomfort.'

Reference

Jim Greenwood, Total Rugby: 15-Man Rugby for Coach and Player, London: Lepus Books, 1978

He may be forced to "take his feet so far back that he goes to ground flat on his face … Even if he doesn't go to ground the position he is forced to adopt allows less and less of the power generated behind him to be transmitted though on to the opposition."

He may be forced to "take his feet so far back that he goes to ground flat on his face … Even if he doesn't go to ground the position he is forced to adopt allows less and less of the power generated behind him to be transmitted though on to the opposition." Alternatively, the prop that is being forced to scrummage too low may "bend forward at the hip, his head gradually getting well below the line of the hip," as in the figure at right.

Alternatively, the prop that is being forced to scrummage too low may "bend forward at the hip, his head gradually getting well below the line of the hip," as in the figure at right. Further on there is a series of images showing the sequence of scrum formation. The final image, reproduced at left shows the engagement. My rough scaling indicates that the loose head prop's hip and knee angles are around 90° and 120° respectively. However it appears that his shoulders are about 15°lower than his hips. This would not only be illegal but would place him and his fellow front rowers in an inherently unstable situation. He is not in a position either to support his own bodyweight or to generate a horizontal shove.

Further on there is a series of images showing the sequence of scrum formation. The final image, reproduced at left shows the engagement. My rough scaling indicates that the loose head prop's hip and knee angles are around 90° and 120° respectively. However it appears that his shoulders are about 15°lower than his hips. This would not only be illegal but would place him and his fellow front rowers in an inherently unstable situation. He is not in a position either to support his own bodyweight or to generate a horizontal shove.