(Article adapted from an assignment submitted in the course, Applied Biomechanics in Strength and Conditioning, in the Masters of Exercise Science (Strength and Conditioning) program at Edith Cowan University)

Abstract

The MyoTruk accommodating resistance machine promotes strength and power training development for the muscle groups responsible for triple extension. The MyoTruk, one of MyoQuip's “Myo-” range of strength equipment, embodies direct-linkage force transmission and replaces the ScrumTruk. Since its introduction in 2004 the ScrumTruk has been routinely used for enhancing the basic strength, muscle mass and explosiveness of rugby union players of all levels and ages. This paper examines the MyoTruk and its capacity to facilitate strength, power and speed development, whilst concurrently comparing it to traditional weight training exercises such as variations of the squat and Olympic type lifts. It examines the MyoTruk’s capacity to enhance the physiological capacities of athletes within the game of rugby union.

Kinematic features and performance characteristics of the MyoTruk

MyoQuip’s mission is to develop fundamentally innovative resistance training equipment with a particular focus on lower body power and core stability development. Each individual machine embodies Broad Biomechanical Correspondence (BBC) technology with a specific focus upon:

1. Strength development exercises that promote the kinematics of triple extension

2. The activation and strengthening of specific muscle groups throughout the entire range of motion

3. The development of speed and power capacities specific to particular sports.

The two most critically distinguishing features of the MyoTruk are the horizontal pushing position of the athlete and the use of MyoQuip's BBC technology, ensuring constantly increasing resistance throughout the range of the exercise movement.

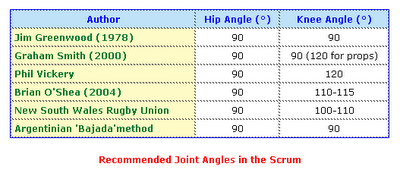

The MyoTruk is a very effective strength and power training alternative and/or complement to the barbell squat in building strength in the gluteal, hamstring and quadriceps muscle groups. In addition to its unique consistent resistance training throughout range the MyoTruk also reduces the compressional forces on lower back that can be attained at times by traditional squatting exercises.(4) Figure 2 below illustrates the biomechanical starting position of the MyoTruk. The hip and knee joint starting angles are able to be adjusted to below 90° if a greater range of movement is desired, but as discussed the integral component of the machine is the ability of the back and spine to maintain normal curvature. (24)

Figure 2: Kinematic and biomechanical features of the MyoTruk - Tom Carter demonstrating starting position for the MyoQuip MyoTruk - note back and shins parallel to ground - hip and knee joint angles at 90º (25)

Figure 3 below illustrates the functional benefits of the MyoTruk as the extension position facilitates the demands of many sports, in particular football codes where extensor strength plays an integral role in the development of speed, power and force characteristics. The triple extension position is able to be attained without the same risks associated with conventional resistance exercise. This perspective is elaborated upon further on within the article.

Figure 3: Tom Carter demonstrating full extension on the MyoQuip MyoTruk - hip and knee joint angles change at same rate. No adverse consequences from attempting to use excessive weight - athlete cannot be trapped under heavy load unlike barbell squat or 45° leg press (25)

The horizontal trunk position stimulates co-contraction of the stabilising muscles of the pelvic and abdominal regions whilst simultaneously providing full-range effective activation of leg extensors from start to complete lock-out.(25) Further, the synchronicity of hip and knee joint angles ensures appropriate distribution of effort between gluteus maximus and quadriceps muscles through extension phases and gluteus and hamstrings during eccentric re-loading phases. The final functional characteristic of the MyoTruk resistance machine is strong activation of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles of the calf during significant dorsiflexion and plantar flexion of the ankle joint.(25)

MyoTruk’s influence on speed and power development

From a training safety and injury prevention perspective the main mechanical advantage of the MyoTruk compared to squat variations lies in its ability to facilitate below parallel (<90º) resistant training throughout range of motion. Compared to the “sticking point” encountered in squat movements, which often occurs at periods when the lifter is moving from a horizontal thigh position through the sticking point (approximately 30º above horizontal).(19,20) The tendency with the squat for excessive trunk lean predominantly occurs at the lowest point of the squat, when the angle at the hip joint is significantly less than at the knee joint.(20) The great difficulty often facing athletes and their coaches is the ability to develop strength and power through range in the lower body with minimal potential of injury occurring.(10)

Triple extension movements in resistance training can be defined as those that involve the extension of the three major joints: hip, knee, and ankle. These three joints, when moved from the flexed to extended position create the explosiveness needed to apply force with the feet against the ground.(8) Extension movements facilitate the main factor involved in the generation of explosive strength. As such it is widely believed that the triple extension is the most important physiological component for enhanced speed-strength training and development. Speed-strength training is a combination of maximum speed and maximum strength, which combined can produce a tremendous amount of force. This force is what we want on the playing field when the foot hits the ground.(8) This has practical applications to sports specific elements such as running the ball into contact in the game of rugby union.

Traditionally it has been proposed that Olympic lifting exercises such as the snatch and clean and jerk variations facilitated the greatest development of triple extension.

Roman and Shakirzyanov (1978) proposed that:

The explosion during an Olympic lifting exercise is executed by the simultaneous action of the muscles of the legs and torso… From this position, the athlete extends his legs and torso and rises up onto his toes and…the shoulders are elevated…Such a position is the most advantageous condition for maximal utilization of the participating muscle groups and the subsequent transfer to the barbell upward.(21)

However the MyoTruk resistance-training machine provides a significant and contemporary alternative to the traditional Olympic lifting methods which have been proposed to enhance triple extension. Not only does the MyoTruk enhance triple extension with increased efficiency of movement; it involves a significantly less intensive time period spent learning complex movement patterns that occur in Olympic weightlifting exercises. The MyoTruk facilitates triple extension development both through traditional strength training paradigms and also dynamically without the same impacts on time limitations of the athlete and coach, the central nervous system and the musculosketal system.

When developing speed and power the muscles of the hip extensors are of the most critical importance because they are usually the weak links in the large majority of athletes.(3) These muscle groups, in particular the glutes, hamstrings, and those of the lower back, are specifically targeted and developed by the MyoTruk. The primary goal of maximal strength exercises is to increase the force or strength producing capabilities of muscles. Through developing strength with various speeds throughout range of motion, the athlete has a subsequent increase in the contractual force producing capabilities of the muscles that are involved in the movement and consequent sporting performance.(3) The MyoTruk allows consistent resistance to be moved throughout range and as such has significant sports specific and functional training connotations. Heavy resistance training results in increases in the contractile rate of force development (RFD), impulse and efferent neuromuscular drive of human skeletal muscle allowing for subsequent transformation into enhanced sports specific speed and power characteristics.(1)

A distinguishing characteristic of the MyoTruk in terms of strength training lies in its ability to be eccentrically controlled so efficiently throughout range whilst the athlete maintains normal lumbar curvature. This has further positive implications for the ability of the MyoTruk to generate strength and power development. Eccentric deceleration is integral in absorbing a load as well as enhancing the elastic potential of the muscle.(14) The elastic energy stored in the series elastic elements (which includes the tendons, the aponeuroses, cross-bridges, actin, myosin filaments and the giant protein Titin) in the eccentric phase is re-used during the concentric phase.(22)

Sports specific connotations: the MyoTruk and the game of rugby union

Dynamic strength is defined as the maximal ability of a muscle to exert a force or torque at a specified velocity.(20) Explosive muscle strength can be defined as the rate of rise in contractile force at the onset of contraction.(1) Rugby union is a dynamic and explosive strength-based sport involving a significant number of collisions both in attack and defence. Successful performance in rugby union is significantly influenced by the physiological capabilities of the athlete; therefore performance can be significantly improved through the implementation of an effective resistance training program. An effective resistance training program should be run in conjunction with dynamic sport specific training. The ability to be able to produce force throughout time (impulse), possess dynamic strength capacities at contact situations and utilise a vast array of different speed attributes are all critical features within the game of rugby union. Figure 4 illustrates the manner in which heavy resistance strength training and ballistic plyometrics have the ability to positively interact with the force time curve and further enhance the strength attributes defined above:

Figure 4: Isometric force: time curve indicating maximal strength, maximal rate of force development, and force at 200 ms for untrained, heavy-resistance strength-trained, and explosive-strength-trained subjects.(11,12)

The MyoTruk resistance-training machine facilitates the development of maximal rate of force development (MFRD) through enhancing the dynamic and explosive strength capacities of the athlete. Through using the MyoTruk both ballistically and through a normal range of speed a variety of aspects along the force/time curve are able to be enhanced. The MyoTruk has the capacity to be used as a vehicle that can extend the force/time curve both vertically and horizontally improving a variety of capacities simultaneously and/or individually. Specifically regarding the game of rugby union, the greater the capacity of the athlete to produce force within the initial <150ms, the greater the ability to create advantageous situations. An enhanced ability to generate speed, power and forceful movements repeatedly over time provides a significant advantage both in attack and defence within a game.(23) This perspective is further enhanced with the continued development of such strong defensive systems and patterns within the modern game leading to the dominance of such orientated teams. However the ability to break these systems down through enhanced physiological capabilities provides a significant opportunity to greatly influence the nature of how the game of rugby union is actually played.(6)

The development of maximal strength of both the agonist and antagonist muscle groups, particularly in the lower limbs is important within the game of rugby union.(26) The role of eccentric strength training in power development was mentioned previously but obviously the strength development of antagonist muscles should not be neglected for athletes who require rapid limb movements, as research suggests enhanced strengthening of the agonist muscles increases both limb speed and accuracy of movement as well as further enhancing positive alterations in the neural firing patterns.(14) This in conjunction with maximal strength training significantly enhances the capacity of the stretch-shorten cycle (SSC).(22)

The MyoTruk effectively enhances power and speed development, and in particular the SSC, through the kinematic structure and motion of the machine not only through eccentric motion but more specifically for the ability to develop sport specific ballistic and explosive extensor strength development as previously discussed after a pre load effect and through a variety of different ranges (above or below 90º in thigh angle). This has practical applications for not only ball carrying and scrummaging facets within the game of rugby union but also at breakdown contests as well.

| • Players covered on average 6,953 m during play (83 minutes). Of this distance, 37% (2,800 m) was spent standing and walking, 27% (1,900 m) jogging, 10% (700 m) cruising, 14% (990 m) striding, 5% (320 m) high-intensity running, and 6% (420 m) sprinting. • Greater running distances were observed for both players (6.7% backs; 10% forwards) in the second half of the game. • Positional data revealed that the backs performed a greater number of sprints (>20 km•h-1) than the forwards (34 vs. 19) during the game. Conversely, the forwards entered the lower speed zone (6-12 km•h-1) on a greater number of occasions than the backs (315 vs. 229) but spent less time standing and walking (66.5 vs. 77.8%) • Players were found to perform 87 moderate-intensity runs (>14 km•h-1) covering an average distance of 19.7 m (SD = 14.6). Average distances of 15.3 m (backs) and 17.3 m (forwards) were recorded for each sprint burst (>20 km•h-1), respectively. • Players exercised at <80 to 85% Vo2max during the course of the game with a mean heart rate of 172 b•min-1 (<88% HRmax) |

Table 1: The physiological demands of the game of Rugby Union (5)

Further, the kinematic motion of the MyoTruk has positive implications on the functional demands of sprinting within the game of rugby union (See Table 1 above) for detail on the physiological demands of the game. The speed at which a player begins to sprint can affect the body position with the game at certain times. Data shows that forwards perform 41% of all accelerations from a standing start, 21% from walking and only 6% from striding.(6) In order to maximise acceleration from a standing start, a low body position is needed. Therefore the ability to generate strength and force in a horizontal fashion throughout range of the exercise provides distinct functional advantages of forwards using the MyoTruk as a resistance-training machine in their particular athletic development. Backs have also been shown to perform 29% of all sprints from a standing start; however they also perform an average of 8 sprints more than forwards do from a striding start.(6)

The ability to generate force off the mark and extensor strength is still critical and thus maximal strength properties obtained through use of the MyoTruk would benefit performance greatly. The type of start initiating the sprints can also affect different muscular recruitment patterns. Short sprints from a standing start involve the quadriceps muscles more and require high relative strength, whereas when a player approaches top speed the hamstrings are strongly recruited.(10) The nature of the game can also affect body positions in preparation to sprint. For example, using a blitz-like defence requires a low body position to maximise speed over 5-10 m. Reactive support play, however, requires a more vertical body position as the player is probably already maximally accelerating to keep pace with the attacking ball carrier.(6)

References

1. Aagaard, P and Andersen, J.L (1998) Correlation between contractile strength and myosin heavy chain isoform composition in human skeletal muscle. Med Sci Sports Exerc 30:1217-1222

2. Astorino, T. and Kravitz, L. (2001) Glycogen and Resistance Training. IDEA Personal Trainer No.4

3. Baggett, K (2007). The Vertical Jump Development Bible. Higher Faster Sports, 3rd Edition.

4. Campbell C. and Muncer, S.J (2005). The cause of low back pain: a network analysis. Social Science and Medicine 60:409–419.

5. Cunniffe, B., Hore, A.J., Whitcombe, M.J., Jones, K.P., Baker, J.S and Davies, B. (2009). Time course of changes in immuneoendocrine markers following an international rugby game. European Journal of Physiology

6. Duthie, G.M., Pyne, D.B., Marsh, D.J. and Hooper, S.L. (2006). Sprint patterns in rugby union during competition. J Strength Cond Res. 20(1):208-14.

7. El-Abd, J. (2005). An objective time-motion analysis of elite rugby union. Sports Medicine, 33(13):973-991.

8. Escamilla, R.F. and Garhammer, J. (2002). “Biomechanics of Powerlifting and Weightlifting Exercises.” Exercise and Sports Science. Eds. Garrett and Kirkendale. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins. p 585-615.

9. Fitts, R.H, Mc Donald, K.S., and Schluter, J.M. (1991). The determinants of skeletal muscle force and power; their adaptability with changes in activation pattern. Journal of Biomechanics 24,1:111-122

10. Francis, C (2002). Charlie Francis 2002 Forum Review, (e-book) available from CharlieFrancis.com

11. Hakkinen, K. and P.V. Komi, 1985a. Changes in electrical and mechanical behaviour of leg extensor muscles during heavy resistance strength training. Scand. J. Sports Sci 7:55-64.

12. Hakkinen, K. and P.V. Komi, 1985b. The effect of explosive type strength training on electromyography and force production characteristics of leg extensor muscles during concentric and various stretch-shortening cycle exercises. Scand. J. Sports Sci 7:65-76.

13. Hutton, R. S (1992). Neuromuscular basis for stretching exercises in Komi ed. Strength and Power Training for Sport, Blackwell, and London.

14. Jaric, S., Rupert, M. Kuok, and D.B.Ilic. (1995) Role of agonist and antagonist muscle strength in rapid movement performances. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 71:464-468

15. Kraemer, W.J and Hakkinen, K (2002). Strength training for sport.

16. Kraemer, W. J and Newton, R. U. (1994). Training for improved vertical jump. Sports Science Exchange, 7(6):1-12

17. McLaughlin, T.M. (1975). A kinematic analysis of the parallel squat as performed in competition by national and world-class powerlifters. Microform Publications. Eugene: University of Oregon, College of Health, Physical Education and Recreation.

18. McLaughlin, T.M., Dillman, C.J. & Lardner, T.J. (1977). A kinematic model of performance in the parallel squat by champion powerlifters. Medicine and Science in Sports, 9:128-33.

19. McLaughlin, T.M., Lardner, T.J. & Dillman, C.J. (1978). Kinetics of the parallel squat. The Research Quarterly, 49:173-89.

20. Moore, R.L and Sully, J.T (1984) Myosin light chain phosphorylation in fast and slow skeletal muscle in situ. Am. Journal of Physiology. 143:257-262.

21. Nindl, B.C., Kraemer, W.J., Marx, J.O., Arciero, P.J., Dohi, K., Kellogg, M.D. and Loomis, G.A. (2001) Overnight responses of the circulating IGF-1 system after acute, heavy resistance training. Journal of Applied Physiology 90:1319-1326.

22. Rimmer, E and Sleivert, G (2000). Effects of Plyometric Intervention Program on Sprint Performance. J Strength Cond Res14(3):295-301

23. Roman, R.A. and M.S. Shakirzyanov. (1978) The Snatch, The Clean and Jerk. Moscow: Fizkultura I Sport, English translation Andrew Charniga Jr. Livonia: Sportivny Press.

24. Ross, B. (2004). Squat or ScrumTruk: which is best for leg extensor training for athletes? http://myoquip.com.au/Squat_or_ScrumTruk.htm

25. Ross, B (2006). A biomechanical model for estimating moments of force at hip and knee joints in the barbell squat. http://www.myoquip.com.au/Biomechanical_model_squat_article.htm

26. White, C (2006). Charlie Francis.Report from 1-1 Internship with Craig White (2nd April – 11th April)

27. Worrell, T.W. (1994). Factors associated with hamstring injuries. Sports Medicine 17:338-345.

28. Wolfe, R.R. (2001). Control of Muscle protein breakdown: effects of activity and nutritional states. International Journal of Sports Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism 11:164-169

Read more...