Thursday, November 20, 2008

Benn Robinson popping Phil Vickery in the scrum

It is the most wonderful feeling when you are the 'popper' and both humiliating and often frightening when you are the 'poppee'. I don't know whether that's a word but it is now.

Read more...

Tuesday, November 18, 2008

At last! A dominant Wallaby scrum

It's been a long time between drinks for the Aussie engine room, and great to see them vindicated after the bagging they copped pre-game from the English press and frontrowers. Considering the improved scrummaging on this tour, perhaps the fact that the Wallabies and all four Australian Super 14 franchises use the ScrumTruk is beginning to pay dividends.

Still one egg doesn't make an omelette, and the Green and Golds have to show they can do it again against the French this weekend. I am not sure that the English front row, Andy Sheridan in particular, are going to be in too good a shape to back up again against the Springboks.

Read more...

Wednesday, April 18, 2007

Some thoughts on engagement under the new rugby scrum law

"With the new scrum engagement rules everybody's looking for that little something to get the advantage. What are your views on my theory that if you use a quick 'squat' on the engage call, this would give you that extra 'bang' and you would be coming in at a rising angle. As there is only a split second to utilise this technique, the player would have to train the stretch-shortening of the muscle.

"Look forward to your thoughts,

"Colin"

I think that Colin is really onto something significant here. What we are observing under the new rules is a tendency to revert to the practice of the No. 8 pulling back on the locks while the referee goes through his " Crouch - Touch - Pause - Engage" chant. On "Engage" the No. 8 pushes with straightened arms against the buttocks of the locks before attempting to wedge his head between the locks' hips.

Prior to the "Engage" the front seven of the pack are pulling forward or leaning forward against the restraint of the No. 8. Once that brake is released they are pitched forward. Apart from the difficulty of coordinating the transmission and timing of force through the three rows of players, there are other problems from a biomechanical viewpoint.

In conventional scrummaging, front rowers typically crouch so that they maintain a stable position while being positioned to generate a powerful shove. By contrast, if they are being pulled backward their natural tendency is to adopt a very different body configuration. They will be more erect, and in particular their hips will be higher. That is what seems to be happening since the introduction of the new law - front rows are falling forward into the engagement with a consequent increase in collapses and resets.

I think that Colin has not thought through issues of timing when he suggests "a quick 'squat' on the engage call". That is far too late in the sequence. However, if around the time of the "Pause" call all forwards crouch or sink, they will be in an ideal position to rapidly generate a cohesive and coordinated upward-slanting shove on the "Engage". The structured and measured sequencing of the referee's calls under the new law makes such a technique very feasible.

What Colin is talking about when he refers to "stretch-shortening" is a phenomenon utilised by jumpers and gymnasts to increase jumping height and also observable in the ballistic back swing or pre-stretch of throwers and racquet game players:

"The stretch-shorten cycle (SSC) describes a period in which a muscle undergoes eccentric work, is stretched, contracts isometrically to stop the counter movement, and follows immediately with maximal contraction with the intention of applying a maximal force. The cycle utilises the principle of stretch reflex, of the length-tension relationship of muscle, storage of elastic energy in the muscle-tendon complex, enhanced potentiation of muscle, and chemical energy from the preload effect." (Doug McClymont and Mike Cron, "Total impact method: a variation on engagement technique in the rugby scrum" http://www.coachesinfo.com/category/rugby/84/)

There is absolutely no doubt that a pack which is trained to utilise stretch-shortening from a low crouch position will generate much more effective and purposeful force than one that one that adopts the "pull-back-then-release-the-brakes" method.

I believe that the new scrum law is potentially a significant improvement, subject to two conditions. Firstly, referees must rigidly enforce Law 20.2 (b) which requires of front rowers that "each player's shoulders must be no lower than the hips". Secondly, the practice of No. 8s pulling back the pack should be outlawed as it has been clearly demonstrated that its effect is directly contrary to the primary intent of the new law, i.e., to produce safer engagements and to minimise resets.

Read more...

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

Body height in the rugby scrum: the value of equal hip and knee joint angles

Despite the undoubted importance of efficient force delivery in the scrum, there is very limited published material addressing the actual dynamics of force delivery.

Powerful scrummaging is dependent on appropriate body position and limb alignment, not just in the relatively static situation immediately after engagement but throughout the entire contest of the scrum. Much of what passes for best practice in scrum formation reflects a failure to critically examine the actual geometry and mechanics of body position and how these change during the scrum contest.

I believe that an optimal configuration of body position and limb alignment on engagement involves hip and knee angles each set at 90° with both trunk and shank being parallel to the ground. During the scrum, hip and knee joints should move synchronously so that their angles remain equal. The hips may sink slightly relative to the shoulders but trunk and shank should remain parallel.

Modern thinking on scrummaging usually advocates consistency of body shape for all participants regardless of position, with the feet approximately shoulder width apart and toes level. There also seems to be general agreement on the need for the trunk to be horizontal or for the shoulders to be slightly higher than the hips. (Greenwood, 1978; Smith, 2000; NSWRU, 2004; Vickery; O'Shea, 2004: Argentinian Bajada method)

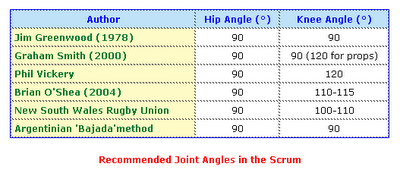

However, when joint angles are discussed there is substantial divergence of opinion on the appropriate angle at the knee joint:

Jim Greenwood, Total Rugby, 1978

More than three decades on Greenwood's book, though overtaken by a succession of Law changes, remains a rugby classic. Its underlying logic is compelling. The figure below summarises his views on body position:

"Thighs approximately vertical. It's obvious that the more acute the angle of the knee the greater the potential range of the drive, but the more strength is required to initiate it. … [Y]ou only have to go into the full-flexed position to realise that a drive from that position is very much slower and more difficult than a drive from a half-squat. Players tend to assume the position in which they feel most capable of a snap drive. On the other hand, the smaller their degree of flexion the smaller the range of drive. For a six-foot player, a flexion of 90° at the knee produces a potential forward movement of about a foot, which allows for a snap drive, and the necessary continuation shove. That is more than enough for all practical purposes, and may well be seen as a maximum."

Greenwood also emphasises pack height:

Smith emphasises body position. "Each player must take up a position by which the force generated by the large muscles of the lower body, the quadriceps and gluteals particularly, can be transmitted effectively and SAFELY through the spine, the shoulders and the neck."

Smith examines the consequences of a prop being experienced enough and strong enough "to alter the height of the scrummage quite legally." and "produce a significant disruption of the opposition scrummage. A prop can thus legally force his opponent to scrummage lower, at a height he finds uncomfortable, and which is mechanically inefficient."

An opponent who is unequal to this pressure will normally react in one of two ways. Firstly, he can move his feet further and further back to relieve the discomfort, as in the figure below:

He may be forced to "take his feet so far back that he goes to ground flat on his face … Even if he doesn't go to ground the position he is forced to adopt allows less and less of the power generated behind him to be transmitted though on to the opposition."

He may be forced to "take his feet so far back that he goes to ground flat on his face … Even if he doesn't go to ground the position he is forced to adopt allows less and less of the power generated behind him to be transmitted though on to the opposition." Alternatively, the prop that is being forced to scrummage too low may "bend forward at the hip, his head gradually getting well below the line of the hip," as in the figure at right.

Alternatively, the prop that is being forced to scrummage too low may "bend forward at the hip, his head gradually getting well below the line of the hip," as in the figure at right. Further on there is a series of images showing the sequence of scrum formation. The final image, reproduced at left shows the engagement. My rough scaling indicates that the loose head prop's hip and knee angles are around 90° and 120° respectively. However it appears that his shoulders are about 15°lower than his hips. This would not only be illegal but would place him and his fellow front rowers in an inherently unstable situation. He is not in a position either to support his own bodyweight or to generate a horizontal shove.

Further on there is a series of images showing the sequence of scrum formation. The final image, reproduced at left shows the engagement. My rough scaling indicates that the loose head prop's hip and knee angles are around 90° and 120° respectively. However it appears that his shoulders are about 15°lower than his hips. This would not only be illegal but would place him and his fellow front rowers in an inherently unstable situation. He is not in a position either to support his own bodyweight or to generate a horizontal shove.

The figure above depicts the limb configurations of a player packed into a scrum with his hip and knee angles both at 90°. (For the sake of illustration I have assumed that the player is 1850mm tall with trunk, thigh and shank lengths of 650mm, 460mm and 480mm respectively.) In order to compare the 90-90 configuration with that advocated by some of the experts listed above, the figure below shows how the body position of the player would change if he retained the 90° hip angle but increased his knee angle to 110°.

Muscles generate most force in the mid range between full extension and full flexion. From a starting point of 90-90 the leg extensors typically remain operating within that efficient range even when the pack achieves a significant shunt forward. Figure 8 illustrates how joint angles change following a push forward of 300mm. As Greenwood suggests, a "forward movement of about a foot ... may well be seen as a maximum" without repositioning of the feet. As can be seen both joint angles have extended to 138°, but this still leaves the players in a position to continue their forward momentum if necessary. Note that both the trunk and shanks have dropped 6° below the horizontal.

Reference

Read more...

Friday, June 09, 2006

Essentials of the Argentinian 'Bajada' rugby scrum

The most obvious characteristic of the Bajada is that second-rowers bind with their external arms around the prop's hip rather than between their legs. But, as explained by Springbok coach Jake White (SARugby.com), one defining characteristic of the method is that "all the power is directed into the hooker. In other words, they scrum along an imaginary arrow drawn pointing inwards from either side of the No 8, which means all the power is directed towards the hooker."

The other defining characteristic is the "Empuje Coordinado" or "Coordinated Push." "The scrumhalf gives a three part call after the "engage". On "pressure" all members of the pack tighten their binds and fill their lungs with air. On the call "one" everyone sinks; the legs at this point should be at 90 degrees. On "two" the pack comes straight forward while violently expelling the air from their lungs. A key note is that nobody moves their feet until forward momentum is established. If the first drive is insufficient the scrumhalf begins the call again and the opposing pack is usually caught off guard and pushed back." Rugby Union from the Virtual Library of Sport

A more detailed explanation of the Bajada was recently published in the World Rugby Forum. It was written by Sergio Espector, a Level 3 coach with Club San Patricio in Buenos Aires. Sergio played for 27 years with the Club and has coached for nearly 20 years. He has kindly given me permission to reproduce his notes which I have reformatted - hopefully without too much distortion of his meaning:

Empuje Coordinado is the resultant of a lot of little details in the way that the props place their feet, the locks bind,and the flankers and the number-eight bind and push too. The eight players push at the same time and in three movements, put all the power to the center of the front row. But the most important thing is that here in Argentina we believe that the scrum is not just another way to put the ball in play.

To have a successful scrum with all eight forwards pushing in a coordinated way, the players' obligations are:

Individual skills

Correct body position

Front row

Second row

Back Row

Pack Technique

We spend a lot of time in training, developing individual and group skills to be able to scrum the way we like, because we think scrum is a strength that not only produces benefits to our forwards' minds, but equally produces collateral damage in our opponents. This is because in the first place their front-rowers and second-rowers lose energy to contribute to open play, and in modern rugby if you don't have 15 players playing all the time you are lost, and in the second place their back-rowers lose speed in defense, because they are busy pushing.

rugby

Bajada

scrum

Read more...

Tuesday, April 25, 2006

Andy Sheridan - an aberration or is prodigious strength the future of rugby?

England's loose-head prop, Andy Sheridan, achieved instant legend status when he demolished Australia's scrum at Twickenham in November. The Wallabies' Al Baxter was firstly sin-binned for his inability to hold his footing, then his replacement, Matt Dunning, was stretchered from the field with a neck injury. The more cynical might wonder how genuine that injury was, but either way it amounted to an acknowledgement that Sheridan was simply much too strong for two experienced international props. He has since been lauded as the strongest frontrower in the world.

The most interesting question is whether his strength is freakish and abnormal or the product of the dedicated application of modern strength training.

There is no doubt that Andrew Sheridan had the genetic endowment to be very big and strong. At Dulwich College, a prestigious south London public school, Sheridan was the dominant player in a team that remained unbeaten from under-11 to first XV. His first rugby master recalled: "Never before have I seen one player inject so much fear into the opposition and dominate so many games with a combination of size, speed and strength."

But the boy was not content simply to exploit his natural advantages. "Everyone was competitive, driving to be better players even at a young age, and that continued right through our time at the school. We used to boost each other. There was a real competitive element. Our training sessions were very hard, and as well as the three rugby sessions each week, lots of players were doing extra weights sessions, extra running, always trying to improve."

The Dulwich years led to an obsession with relentless weights training: "Weight training was something I have always enjoyed. Something I got a high from doing. There is definitely something addictive about it. That's partly down to the improvement you can see, but it's also to do with how you feel afterwards.

"They talk about endorphins or something being released - not that you can go and pick up your car after a hard session, but you do feel good. I liked the feeling of being able to shift a weight that to the average person seems very heavy. It's whatever works for you."

While playing for Richmond and later the Bristol Shoguns, Sheridan did many extra sessions in the gym, striving to become massively strong. He set himself a target of bench-pressing 500lbs (227kg), eventually achieving 215kg. "The weightlifting wasn't directly related to rugby, but if I reach a goal like that, I am going to be more confident."

He has since acknowledged "Getting strong on the bench press won't necessarily make me play rugby any better. ... Perhaps when I was 19 or 20 it was more of an ego thing trying to bump it up, but I've gotten over that now." His focus has shifted to improving leg strength and back strength.

Sheridan's forwards coach at Sale, Kingsley Jones, says "I've been in rugby all my life, and he's the strongest guy I've come across in the game or outside it. And he's so dynamic with it. ... He can do the fast exercises; he can do the strong exercises. He's just an incredible athlete."

Sale's fitness coach, Nick Johnston, believes that Sheridan has not yet reached his full strength potential. "From a trainer's point of view," he says, "he could probably improve another 25 to 30%. Which is quite frightening."

If he had not developed a preoccupation with strength training, Andy Sheridan would still have developed into a big and powerful rugby player but almost certainly not one who would have reached the international level. His example suggests that players with appropriate genetic endowment can achieve massive strength specific to the demands of their sport through the long term application of strength training techniques. However, in order to do so, these players currently have to almost defy the rugby world's orthodoxy in relation to strength and conditioning.

There is a general failure to recognise firstly that rugby players are typically not particularly strong given their size and secondly that superior dynamic strength can yield huge advantage in the sport of rugby. However, the gradual recognition and exploitation of these truths is beginning to revolutionise the game.

rugby

scrum

Andy Sheridan

frontrower

Dulwich College

Richmond rugby

Bristol Shoguns

Read more...

Sunday, March 19, 2006

A solution to uncontested rugby scrums?

Uncontested scrums "change the shape of the game and the dominant scrum is effectively depowered. Furthermore, without the contest and the need to scrummage, back row players are free to close down space ... ." However, there is little that a referee can do to prevent manipulation of the law. "From a match official's perspective. if a coach, physio or player indicates that he is injured then he is injured. In terms of safety, it is as simple as that."

Lander points out that the law requires that "both teams must provide front row cover within the 22 players selected to replace the hooker on the first occasion for injury, blood, sin bin or sending off. Similarly, for either, but not both props on the first occasion for the same reasons."

"A coach has complied with law if he has replaced a hooker and prop on the first occasion. If the team cannot provide a suitably trained player for a subsequent injury to a prop or hooker" he is entitled to request uncontested scrums.

I suggest that the problem can be virtually eliminated at least at the professional level by requiring teams to nominate a 23rd player as "designated front row substitute." The player would have to be physically capable of taking any of the front row positions.

The designated substitute would only be entitled and required to take the field if the normal substitution possibilities for either hooker or prop positions had been exhausted. The first circumstance in which they would enter the game would be if both the hooker and the reserve hooker had left the field "for injury, blood, sin bin or sending off." The other circumstance would be if two of the three players chosen as props or reserve prop had left the field for any of the same reasons.

If such a requirement were introduced, uncontested scrums would be almost eliminated and the opportunity for coaches of teams with inferior scrums to exploit the laws would be removed.

rugby

scrum

Steve Lander

Read more...

Tuesday, January 31, 2006

Why do rugby players scrum and maul at such different body heights?

Scrums and mauls are the two great dominance contests within the game of rugby. Marked superiority in either of these forms of engagement can affect the morale of both teams in a way that a corresponding supremacy at say the lineout does not.

Forward packs spend countless hours developing scrum technique but very much less attention is given to the maul, particularly in a defensive situation. Scrums are also elaborately structured whereas mauls tend to be chaotic. To a large extent this is due to the relative extent to which the two are regulated by the Laws of Rugby. Law 20, relating to the scrum, comprises three times as many pages as Law 17 pertaining to the maul.

Unlike the scrum, the Laws are largely silent on what players can do in the maul. Within the maul itself the most relevant clauses are that "Players joining a maul must have their heads and shoulders no lower than their hips" (17.2 (a)); they "must endeavour to stay on their feet" (17.2 (d)); and "A player must not intentionally collapse a maul" (17.2 (e)). Thus there remains considerable latitude for creativity.

One very marked difference between the two contests is that in the scrum either pack, whether having the feed or not, has the opportunity to establish dominance and drive the other pack back. By contrast it is very rare in the maul for the side not in possession to gain significant ground. This is largely due to the fact that the team with the ball is able to surreptitiously transfer the ball laterally from hand to hand so that the push from their opponents bypasses the ball-carrier, allowing him to be driven forward more or less unimpeded.

I believe that players can be trained to maul much more effectively and the secret is body height. Note the photo reproduced from the International Rugby Board's online version of the Laws of Rugby. It is intended to show the player involvements necessary for a maul to be formed. But it is also very instructive in illustrating body heights typically adopted in the maul. The ball carrier is standing upright, making no attempt to crouch. His team mate in attempting to seal off the ball has his shoulder at chest height of the ball-carrier. Their opponent has bound on the ball-carrier at waist height. None of these players have their legs positioned to exert an effective forward shove.

The body height adopted by the first players engaging from each team usually defines the height of their side of the ensuing maul. Subsequent players typically bind against the buttocks of the players in front of them. Players arriving at a maul tend to simply bend at the waist when joining the contest.

Compare the likely height of this maul with the body height of the same players in a scrum situation. It can be confidently anticipated that body heights would be at least 300mm lower in a scrum than in a maul.

If the defending player in the photo were to bind around the thighs of his opponent rather than the waist, he would create a platform for his team mates to bind at something close to scrummaging height. Each of the players is then likely to have optimal hip and knee joint angles for generating forward momentum. It might even be advantageous for players to adopt the second-rower's technique of binding between the thighs of the player in front, whether team mate or foe. The one essential requirement is that players packing low secure a very firm grip to avoid being penalised for going to ground.

While front row players in the scrum are prohibited from "lifting or forcing an opponent up" (20.8 (i)), there is no corresponding restriction in relation to mauls. Although lifting is treated as "dangerous play" in the scrum, it does not have the same connotation in the maul where players are bound in an unstructured way and not confined or compressed as in the scrum. With his shoulder under his opponent's buttocks a player is ideally placed to drive up, forcing the opponent to give ground.

While mauls are often formed in an unstructured way, many of them emerge from static engagements such as the lineout or where the ball is being contested after a tackle. In such a situation a well-drilled team would have the opportunity to rapidly adopt a pseudo-scrum formation and drive forward. Not only are they likely to gain advantage in that particular maul, but the practice of adopting biomechanically superior body positions will undoubtedly be energy-conserving over the course of a game.

rugby

rugby scrum

rugby maul

bodyheight

Laws of Rugby

Read more...

Tuesday, January 24, 2006

The benefits of explosive strength training for rugby football

Rugby football involves prolonged physical engagements between players where they are subjected to loading substantially greater than their own body weight. An ability to very rapidly generate force is advantageous in these areas of physical engagement. In addition to basic strength training, players need to undertake activity-specific training for explosive strength.

Unlike other forms of football, rugby can be usefully viewed as a succession of prolonged physical engagements, either between individual players or between groups of players. Each of these engagements demands the exercise of substantial physical strength. While basic strength training should form the foundation for such engagements, there should also be a focus on developing explosive strength appropriate to the particular activity.

During the extended periods when players are physically contesting with their opposing counterparts they are continually subjected to loading substantially greater than their own body weight. And, because that added resistance is live, there is often the problem of overcoming not only inertia but also counter force triggered by an initiating movement

In modern rugby considerable attention is given to fitness and aerobic conditioning as well as basic weight training, but there is very limited focus on the development of activity-specific explosive strength. This is despite the fact that an ability to very rapidly generate force can yield a competitive advantage in each of the areas of physical engagement in rugby:

Scrum and maul In the scrum or maul situation it is very difficult to shunt the opposing pack backward unless there is synchronised explosive activity. If a pack begins to move forward slowly or if just one or a couple of players attempt to initiate a shove, they are unlikely to be able to overcome the inertia of the opposing pack's body mass. In addition, the attempted drive forward will almost certainly trigger an almost immediate counter-shove. On the other hand if a pack suddenly and explosively begins to drive forward as a synchronised, coordinated unit, they are likely to be able to generate momentum and place their opponents on the back foot.

The key elements are that each of the forwards possess basic strength and a capacity to rapidly generate force. However, it is essential that their movements be synchronized. If any of these elements of strength, explosiveness and synchronicity are lacking the attempt is likely to prove futile or even counterproductive.

Tackle In a tackle situation there is great advantage in forcing the opponent, whether ball-carrier or tackler, back from the line of engagement. In order to do this effectively, the action has to be both powerful and virtually instantaneous.

In addition, ball-carriers with explosive leg drive are often able to brush past attempted tackles, while tacklers with similar attributes can forcefully secure the ball-carrier and take him to ground.

Ruck At the breakdown of play following a tackle the ability to push back or "clean out" opposing players from the ruck offers opportunities to win the contest for the ball or at least put the opposing team in a disadvantageous situation. The only effective way to win the breakdown contest is to apply very considerable force in an explosive manner.

Lineout The outcome of the lineout contest is largely dependent on how high the jumper can ascend, but also on how rapidly he can reach that point. This requires not only a very good vertical leap by the jumper, but also the ability of his support players to forcefully elevate him. Both jumping and lifting require specific forms of explosive strength.

When forward packs are evenly matched in strength and technique, and defensive techniques are well-coordinated, a game of rugby can often become a war of attrition, with teams attempting to wear one another down over the course of the game. It is very difficult to maintain concentration and alertness throughout an 80-minute game, and a capacity for explosive action allows the exploitation of fatigue and inattention. It provides surprise and unpredictability, while limiting the possibility of appropriate reaction.

Strength training for rugby should always be grounded on a solid foundation of basic strength; but coaches who are seeking to gain a sustainable competitive edge would do well to incorporate a comprehensive program of activity-specific training for explosive strength.

rugby

rugby training

strength training

explosive strength

basic strength

Read more...