skip to main |

skip to sidebar

[Summary:

The body height of rugby players in mauls tends to be very much higher than in scrums. High body positions are inefficient for generating forward momentum. There would be advantages in training players to pack at thigh height rather than waist height. Not only are they likely to gain dominance in the maul, but the practice of adopting biomechanically superior body positions is energy-conserving over the course of a game.]

Scrums and mauls are the two great dominance contests within the game of rugby. Marked superiority in either of these forms of engagement can affect the morale of both teams in a way that a corresponding supremacy at say the lineout does not.

Forward packs spend countless hours developing scrum technique but very much less attention is given to the maul, particularly in a defensive situation. Scrums are also elaborately structured whereas mauls tend to be chaotic. To a large extent this is due to the relative extent to which the two are regulated by the Laws of Rugby. Law 20, relating to the scrum, comprises three times as many pages as Law 17 pertaining to the maul.

Unlike the scrum, the Laws are largely silent on what players can do in the maul. Within the maul itself the most relevant clauses are that "Players joining a maul must have their heads and shoulders no lower than their hips" (17.2 (a)); they "must endeavour to stay on their feet" (17.2 (d)); and "A player must not intentionally collapse a maul" (17.2 (e)). Thus there remains considerable latitude for creativity.

One very marked difference between the two contests is that in the scrum either pack, whether having the feed or not, has the opportunity to establish dominance and drive the other pack back. By contrast it is very rare in the maul for the side not in possession to gain significant ground. This is largely due to the fact that the team with the ball is able to surreptitiously transfer the ball laterally from hand to hand so that the push from their opponents bypasses the ball-carrier, allowing him to be driven forward more or less unimpeded.

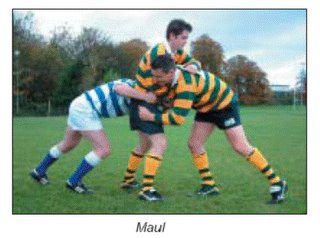

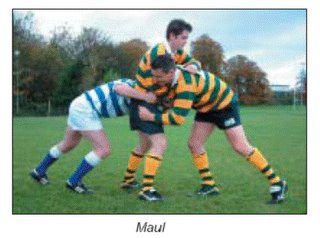

I believe that players can be trained to maul much more effectively and the secret is body height. Note the photo reproduced from the International Rugby Board's online version of the Laws of Rugby. It is intended to show the player involvements necessary for a maul to be formed. But it is also very instructive in illustrating body heights typically adopted in the maul. The ball carrier is standing upright, making no attempt to crouch. His team mate in attempting to seal off the ball has his shoulder at chest height of the ball-carrier. Their opponent has bound on the ball-carrier at waist height. None of these players have their legs positioned to exert an effective forward shove.

The body height adopted by the first players engaging from each team usually defines the height of their side of the ensuing maul. Subsequent players typically bind against the buttocks of the players in front of them. Players arriving at a maul tend to simply bend at the waist when joining the contest.

Compare the likely height of this maul with the body height of the same players in a scrum situation. It can be confidently anticipated that body heights would be at least 300mm lower in a scrum than in a maul.

If the defending player in the photo were to bind around the thighs of his opponent rather than the waist, he would create a platform for his team mates to bind at something close to scrummaging height. Each of the players is then likely to have optimal hip and knee joint angles for generating forward momentum. It might even be advantageous for players to adopt the second-rower's technique of binding between the thighs of the player in front, whether team mate or foe. The one essential requirement is that players packing low secure a very firm grip to avoid being penalised for going to ground.

While front row players in the scrum are prohibited from "lifting or forcing an opponent up" (20.8 (i)), there is no corresponding restriction in relation to mauls. Although lifting is treated as "dangerous play" in the scrum, it does not have the same connotation in the maul where players are bound in an unstructured way and not confined or compressed as in the scrum. With his shoulder under his opponent's buttocks a player is ideally placed to drive up, forcing the opponent to give ground.

While mauls are often formed in an unstructured way, many of them emerge from static engagements such as the lineout or where the ball is being contested after a tackle. In such a situation a well-drilled team would have the opportunity to rapidly adopt a pseudo-scrum formation and drive forward. Not only are they likely to gain advantage in that particular maul, but the practice of adopting biomechanically superior body positions will undoubtedly be energy-conserving over the course of a game.

rugby

rugby scrum

rugby maul

bodyheight

Laws of Rugby

Read more...

[Summary:

Rugby football involves prolonged physical engagements between players where they are subjected to loading substantially greater than their own body weight. An ability to very rapidly generate force is advantageous in these areas of physical engagement. In addition to basic strength training, players need to undertake activity-specific training for explosive strength.]

Rugby football involves prolonged physical engagements between players where they are subjected to loading substantially greater than their own body weight. An ability to very rapidly generate force is advantageous in these areas of physical engagement. In addition to basic strength training, players need to undertake activity-specific training for explosive strength.

Unlike other forms of football, rugby can be usefully viewed as a succession of prolonged physical engagements, either between individual players or between groups of players. Each of these engagements demands the exercise of substantial physical strength. While basic strength training should form the foundation for such engagements, there should also be a focus on developing explosive strength appropriate to the particular activity.

During the extended periods when players are physically contesting with their opposing counterparts they are continually subjected to loading substantially greater than their own body weight. And, because that added resistance is live, there is often the problem of overcoming not only inertia but also counter force triggered by an initiating movement

In modern rugby considerable attention is given to fitness and aerobic conditioning as well as basic weight training, but there is very limited focus on the development of activity-specific explosive strength. This is despite the fact that an ability to very rapidly generate force can yield a competitive advantage in each of the areas of physical engagement in rugby:

Scrum and maul In the scrum or maul situation it is very difficult to shunt the opposing pack backward unless there is synchronised explosive activity. If a pack begins to move forward slowly or if just one or a couple of players attempt to initiate a shove, they are unlikely to be able to overcome the inertia of the opposing pack's body mass. In addition, the attempted drive forward will almost certainly trigger an almost immediate counter-shove. On the other hand if a pack suddenly and explosively begins to drive forward as a synchronised, coordinated unit, they are likely to be able to generate momentum and place their opponents on the back foot.

The key elements are that each of the forwards possess basic strength and a capacity to rapidly generate force. However, it is essential that their movements be synchronized. If any of these elements of strength, explosiveness and synchronicity are lacking the attempt is likely to prove futile or even counterproductive.

Tackle In a tackle situation there is great advantage in forcing the opponent, whether ball-carrier or tackler, back from the line of engagement. In order to do this effectively, the action has to be both powerful and virtually instantaneous.

In addition, ball-carriers with explosive leg drive are often able to brush past attempted tackles, while tacklers with similar attributes can forcefully secure the ball-carrier and take him to ground.

Ruck At the breakdown of play following a tackle the ability to push back or "clean out" opposing players from the ruck offers opportunities to win the contest for the ball or at least put the opposing team in a disadvantageous situation. The only effective way to win the breakdown contest is to apply very considerable force in an explosive manner.

Lineout The outcome of the lineout contest is largely dependent on how high the jumper can ascend, but also on how rapidly he can reach that point. This requires not only a very good vertical leap by the jumper, but also the ability of his support players to forcefully elevate him. Both jumping and lifting require specific forms of explosive strength.

When forward packs are evenly matched in strength and technique, and defensive techniques are well-coordinated, a game of rugby can often become a war of attrition, with teams attempting to wear one another down over the course of the game. It is very difficult to maintain concentration and alertness throughout an 80-minute game, and a capacity for explosive action allows the exploitation of fatigue and inattention. It provides surprise and unpredictability, while limiting the possibility of appropriate reaction.

Strength training for rugby should always be grounded on a solid foundation of basic strength; but coaches who are seeking to gain a sustainable competitive edge would do well to incorporate a comprehensive program of activity-specific training for explosive strength.

rugby

rugby training

strength training

explosive strength

basic strength

Read more...