In recent days there has been discussion among some who use their blogs as weight training diaries about difficulties with squatting. The author of A prop's journey talks about "the quarter and half squats I'm stuck with at the moment because my leg/back/ankle (it's all connected) flexibility is terrible."

And then we have Scott Bird posting in 99 shades of grey >> straight to the bar that "there was going to be some work to do" in order to reach parallel in the squat which he conceded he was "nowhere near." This was confirmed by a photo showing his inability to descend to the parallel position even with an unloaded bar. I hope that Scott doesn't mind me reproducing that photo in order to illustrate some of my own ideas on squatting.

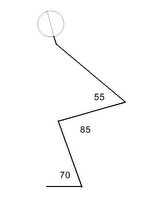

I have endeavoured to estimate his joint angles from that image and I trust that the first stick-figure diagram is a reasonable approximation. Not to put too fine a point on it, Scott's squat technique looks ugly and uncomfortable.

The first problem seems to be very limited ankle flexion as indicated by the fact that he is having difficulty getting the angle between his shanks and the horizontal below 70°. You have to wonder whether he does much calf work and if so whether he trains full range. Most people who exercise their calves only do plantar flexion - raising their heels from the floor - and never attempt dorsiflexion - lifting their toes.

But the main problem appears to be with his knee flexion; by my estimate he seems unable to flex the joint below 85°. The apparent 30° difference between his flexion at the knee and the hip is indicative of very poor squatting technique. A number of things flow from this. Firstly he is only activating the quadriceps group through the top half of contraction, i.e., from 85° to 180° of knee joint angle - he is missing out on at least 50° of movement through the most vital range. One can almost guarantee that he has poor leg extensor strength.

Note that he is working his hip joints through a much greater range. Basically for Scott the squat is only really a glute exercise, and to the extent that he was able to attempt heavy poundages he would be likely to impose severe loading on the lumbar region of his back.

We can also see that until he learns to further flex his ankle and knee joints he cannot really take a loaded bar much lower than in the photo. This is because of the gravitational necessity to keep the bar directly above his feet. If he flexed his hips much more he would begin to lose balance.

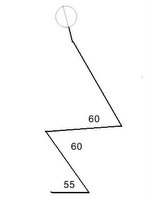

Compare Scott's articular geometry with that of the second stick-figure. Biomechanically there is no comparison - the second figure looks comfortably balanced with the gravitational path of the weight bar passing through the midline of the feet. Greater ankle flexion is a contributing factor but the most important point to note is the symmetry between hip and knee joint angles. In fact an exerciser adopting this posture would probably have synchronicity between these angles through the whole range of movement. As a result the shanks and back remain parallel and there is no adverse loading on the spine. The weight of the bar is always directly above the feet and both the quadriceps and gluteus maximus are being worked through their full range.

The first advice that I would give Scott would be to concentrate on keeping his back more erect. This would almost certainly lead him to flex his ankles more thus shifting his knees forward. It will probably feel uncomfortable at first as his quads are not used to being asked to do any serious work.

I suspect that many people fall into the habit of excessive forward trunk lean from observing power lifters. However a typical power lifter is probably someone with a very strong back who is focussed on muscling up maximum weight without being concerned as to whether they are adequately exercising their leg extensors.

In any case a 1978 study (McLaughlin, T.M., Lardner, T.J. & Dillman, C.J. Kinetics of the parallel squat. The Research Quarterly, 49, 173-89. 1978) of nationally-ranked and world-class powerlifters identified a tendency for less-skilled subjects to exhibit greater trunk torques than more highly-skilled subjects. "It would appear from the data that high-skilled subjects attempt to minimize the trunk torque, and do so largely by reducing forward trunk lean." It was noted that among the subjects, the then world super heavy weight champion maintained the greatest trunk angle of all subjects and, despite his much greater bar load, had a lower trunk torque than many smaller, less-skilled subjects.

The high-skilled subjects demonstrated larger trunk angles, lower trunk torques and more extensor-dominant thigh torques. "It therefore appears that the high-skilled subjects strive to use the leg extensors to a greater extent than do less skilled subjects. This greater emphasis on the leg extensors is obtained by a minimization of the trunk torques by the high-skilled subjects (achieved by maintaining more erect trunk positions)."

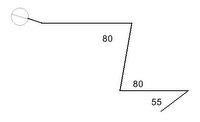

The final stick-figure shows a typical starting position for an exerciser using the ScrumTruk. So long as they are instructed to pack low against the shoulder pads and keep their hips low they tend to automatically have their backs and shanks parallel and consequently achieve and maintain synchronicity between their hip and knee joint angles. An almost universal observation from athletes using the ScrumTruk for the first time is that they have a definite "burn" or "pump" effect in the quadriceps indicating that the device is very much leg extensor specific. The apparatus also encourages them to significantly dorsiflex their ankles.

Our observation from two years of athletes using the ScrumTruk is that its techniques and balanced development of the hip and leg extensors transfer well across to the barbell squat - athletes with extensive Scrumtruk experience tend to subsequently show very good form and depth on the squat.

squat

powerlifter

ScrumTruk

Tuesday, August 15, 2006

The role of synchronised hip and knee joint angles in efficient squatting

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

3 comments:

Nice and thorough - and thanks for the excellent advice. To clarify a couple of things (your estimates were spot-on by the way) :

I do little to no calf work. I found that in a follow-up session to the one in which I was photographed, a little shin stretching before the squats definitely helped. This would indicate that you're right - a bit of calf work, and a spot of stretching, would be of great benefit.

The knee flexion (or lack thereof) is something I hadn't really considered, and if you have any suggestions on improving this I'm very keen to hear them.

Regarding the heavier squatting loads, I definitely do use my lower back to muscle-up the weight rather than good squatting technique. I suspect I've been doing this for years (not that it's a good thing) - my deadlift is much smoother and stronger than my squat.

Learning squat technique from observing powerlifters - yes, this is exactly what happened in my case. No doubt I would benefit from learning a high-bar narrow-stance technique first, before learning the low-bar sumo-stance powerlifter method.

As to my form being 'ugly and uncomfortable', it feels that way. As I said, it's going to be a long - but important - journey.

A quick update : I've dedicated Friday workouts to relearning the squat, and included a bit of calf work with the stretching and bodyweight squatting (as well as the real thing). Thanks again.

We're really going to have to get you out to Sydney Uni to try out some machines and post a couple of road tests, Scott. Yesterday we installed the HipneeThrust, a supine leg press that can be used from extreme positions of hip and knee joint flexion.

I intend to have the announcement post up tomorrow. We'll get your joint flexibility right yet.

Regards

Bruce

Post a Comment